Dr. Mark Sager

For Dr. Mark Sager, a backyard conversation sparked an idea that gave birth to the Wisconsin Registry for Alzheimer’s Prevention (WRAP). For Dr. Sanjay Asthana, a visit with his ailing father fueled his passion to pinpoint risk factors and causes and lead research into possible treatments for Alzheimer’s disease.

The efforts of their research teams at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health are providing rays of hope and new understanding in the fight against the deadly disease.

Every day, more families are experiencing the ravages of Alzheimer’s. About 5.3 million Americans suffer from the disease, and that number is expected to exceed 13 million by the year 2050. The average life span from the point of diagnosis to death is eight to nine years, although some people may live up to 20 years.

Alzheimer’s research at the UW-Madison is advancing on many fronts. An overflow crowd in April learned about many aspects of that work at “Mini-Med School: Aging Brain and Alzheimer’s Disease: What’s Normal and What’s to Worry About,” which featured research and clinical highlights spearheaded in Wisconsin.

Passion and concern can be seen in the number of individual and foundation donors backing Alzheimer’s research efforts. Lou Holland Sr. (’65 BS CALS) has made gifts toward research, and his son Lou Holland Jr. (’86 BA L&S) has shown strong support for the family’s Holland Wisconsin Alzheimer’s Institute Research Fund in support of WRAP. The Helen Bader Foundation has supported the Wisconsin Alzheimer’s Institute from its conception. Other individuals have stepped forward with heartfelt gifts large and small, some unsolicited.

From idea to national model

Sager was sitting in the backyard with his wife, Mollee, in the late ‘90s. At the time, there was little Alzheimer’s disease research being done at the School, and he realized a program was needed. “The question was, ‘Who do you study?’ And Mollee said, ‘You need to study me,’ because her mother had developed Alzheimer’s disease.”

He noted that at the time, Alzheimer’s was considered an old person’s disease. “That’s analogous to saying you can only study heart disease by studying those with heart attacks,” Sager said. “That’s just not true. “

“We have a unique public health mission dedicated to improving the quality of care provided to Wisconsinites affected by this disease.”

Dr. Mark Sager

The realization that Alzheimer’s could have a long gestation period led Sager and colleagues to establish WRAP, which started recruiting people between 40 and 65 years old with a family history of Alzheimer’s. That registry now includes more than 1,500 participants in Wisconsin and 19 other states and is internationally known as a pioneering study in prevention research. WRAP is being copied all over the world, including as far away as Israel.

A memory diagnostic clinic network affiliated with the Institute has stretched into rural communities and Milwaukee, affecting the lives of thousands.

“We were started as a partnership between the state of Wisconsin, the Helen Bader Foundation and the School of Medicine and Public Health,” he said. “We have a unique public health mission dedicated to improving the quality of care provided to Wisconsinites affected by this disease.

Suzanne Bottum-Jones oversees the memory diagnostic clinic outreach across Wisconsin. Diagnosing Alzheimer’s is a huge challenge. “Fourteen years ago, Dr. Sager and the public health side of this office were able to design a policy and guidelines on the best way to diagnose and manage memory issues,” she said. Statewide, 44 clinics are part of the network.

Some minority communities are especially vulnerable to Alzheimer’s. “The Bader Foundation recognized that African-Americans suffer from Alzheimer’s disease in numbers disproportionally larger than other communities,” said Gina Green-Harris, the Institute’s director of Milwaukee outreach. “They charged us with creating community outreach and education and building awareness around Alzheimer’s disease, but also to go a step further and really help with African-Americans being diagnosed and getting into treatment earlier.”

Janet Rowley is the research program manager overseeing WRAP. “I’m multigenerational. I have Alzheimer’s in the family,” she said. “I want nothing more than for us to be able to find answers. Our participants are the same way; they want answers. I went through that nightmare of having a parent go through this and having no support.”

WRAP has sites in La Crosse, Milwaukee and Madison. Not all have Alzheimer’s in the family; a control group contains about 450 people. “Most people will tell you, if an answer is not available for my generation, I want it for my children,” she said.

A father’s struggle

For Dr. Sanjay Asthana, the fight is personal as well. Some years ago, he saw something was not right with his father.

Madan Mohan-Sahai Asthana was an economist working as a United Nations diplomat in Africa. “During the last few years of his job, he and my mother noticed some very early memory problems,” Asthana said. “He was in his early 60s. Although the UN wanted him to stay, he decided to return to India.”

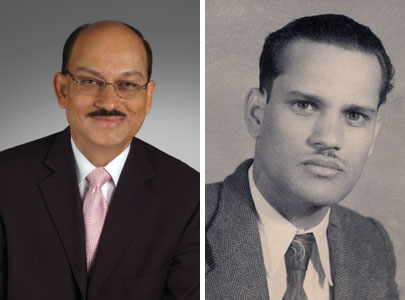

Dr. Sanjay Asthana, left, director of the Wisconsin Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center, detected signs of the disease in his diplomat father, Madan Mohan-Sahai Asthana, right.

The younger Asthana, then a trainee in Alzheimer’s disease research at the National Institutes of Health, started to pick up signs during later visits. “I experienced the usual denial; he’s your father and a learned man. I said, ‘No, no, maybe it’s stress. Maybe he’s unhappy he took retirement early.’ I discounted it, even though I knew there were issues.”

Two years later, his father’s decline was clear. “I basically diagnosed him. He lived with it for 18 years and suffered every stage of Alzheimer’s disease,” Asthana said. “The last two years, you don’t wish on anyone. They were very, very tough.”

That experience has driven Asthana, director of the Wisconsin Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (ADRC) since 2008, in leading his team of researchers and clinicians in quests to identify Alzheimer’s earlier in patients and work toward new treatments and, perhaps one day, a possible cure. “You see so much suffering, and I’ve seen it on a very personal level,” he said. “Let’s do something.”

The ADRC combines the forces of the School of Medicine and Public Health and the Geriatric Research, Education and Clinical Center (GRECC) of the William S. Middleton Memorial Veterans Hospital in Madison, where Asthana is located.

Sager also is associate director of the ADRC. “Dr. Sager and I have joined all our resources, our expertise, our passion to develop a very solid, well-known Alzheimer’s program,” Asthana said in his office at the VA hospital.

“Our program is very extensive, interdisciplinary and transdepartmental, and it involves people with all kinds of backgrounds,” Asthana said. “We have social scientists, lab-based scientists, neuropsychologists, physicians, basic scientists, statisticians, pathologists, education experts.”

The gerontologists at GRECC fill a unique niche. Their work with aging populations is critical in dealing with dilemmas such as falls and swallowing problems, which can lead to pneumonia, among other complications.

Growing optimism

At an international conference this year in Vancouver, Canada, a number of new findings were spotlighted. “Over the last 30 years or so, a lot of research has gone into understanding what causes Alzheimer’s,” Asthana said. “We don’t still understand the full picture; it’s not a single-cause disease like diabetes, where if you have insulin problems, you will become diabetic. With Alzheimer’s, there are multiple reasons and pathologies that go on in the brain.

“We understand some reasons, not all,” he said. “That is one of the reasons why we don’t have a cure.”

In building its program, the ADRC has attracted many young researchers who are rising stars in their fields.

“We have a lot of relatively young researchers, and most of them are contacted once or twice a month by other universities seeking them for lucrative positions,” he said. “They have stayed because of the passion for what goes on here and the unique research opportunities. We have been able to use some philanthropic funds to retain them.”

As the U.S. population ages, the push to overcome Alzheimer’s disease will intensify.

“We don’t have the cure,” Asthana said. “But we are very hopeful that in the next five to 10 years we could see a huge breakthrough if we’re able to fund enough research and if enough people enroll in our studies.”