Vikram Adhikarla is the recipient of the Joseph Dillinger Award for Teaching Excellence.

When Theodore “Ted” Cohen (’60 BS L&S, ’61 MS L&S, ’66 PhD L&S) published his first novel, “Full Circle,” he mailed it to the University of Wisconsin-Madison Department of Physics with a check and a note, reading, “In partial repayment of a debt long overdue.”

Cohen explained that it was Professor of Physics Joseph Dillinger who had challenged him to change majors from engineering to physics, a decision that altered the course of his life. It turns out that the late Professor Dillinger was influential in the lives of many, and the Joseph R. Dillinger Teaching Award has been given annually since 1996 to an outstanding graduate student teaching assistant in the Department of Physics. The award is supported by contributions from the Dillinger family and others like Ted Cohen.

Dillinger grew up on a farm outside Carbondale, Illinois, the first in his family to graduate from high school. In the early 1940s, he earned a bachelor’s degree at Southern Illinois University, met and married Martha Freeman and came to UW-Madison to pursue graduate studies in physics. While in Madison, he was drafted by his local Illinois draft board, which did not support educational deferment. At the same time, an Army recruiter arrived in Madison looking for University graduates to join the team working on wartime research and development at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). The Department of Physics identified Dillinger as nearing completion on a PhD and beginning an Army obligation; the Army reassigned Dillinger to the MIT Radiation Lab, where he worked on radar technology that became instrumental to the success of Allied forces.

Joe and Martha Dillinger returned to UW-Madison, where Joe received his PhD in 1946 and then joined the faculty of the Department of Physics. The Dillinger home became a hothouse of learning for their three children. Martha Dillinger was a high school teacher and fully supportive of what some might view as unusual family activities. Summer vacations in the 1960s often included road trips in the station wagon with children, luggage and dewars of liquid nitrogen and helium; destinations were often National Science Foundation summer institutes for high school teachers and top students, where Dillinger would demonstrate principles of low-temperature physics. His signature demonstration was “drinking” liquid nitrogen and exhaling the cloud of evaporating liquid. Back at home, dinner could readily become a lecture by the children on the topic of what they’d learned in school that day, illustrated on the full-size slate blackboard Dillinger had installed on a dining room wall. All three of the Dillinger children earned undergraduate degrees from the University.

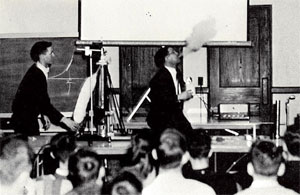

Professor Dillinger was a tireless ambassador for the sciences. Here, he exhales liquid nitrogen during a demonstration at Madison West High School.

Dillinger was active in the American Association of Physics Teachers, a faculty advisor for Phi Sigma Delta fraternity and especially enjoyed teaching a physics course for non-majors. He loved questions and he loved to share the scientific explanation.

Dillinger was at a fraternity event when he ran into student Ted Cohen, and they began a conversation about low-temperature physics. Dillinger urged Cohen to major in the discipline, but Cohen protested that he couldn’t leave engineering or he would lose 29 credits. At a meeting a day or so later, Dillinger told Cohen bluntly that he had a decision to make. “You can give up a year now… and do something you love, or you can continue with what you are doing and end up with a career in an area that makes you unhappy.”

Cohen transferred to the College of Letters & Science to major in physics—losing 29 credits—and was never happier. In meeting the requirements of his new major, he enrolled in English literature and geology, two areas of study that later proved key to Cohen’s career and avocations.

By the late 1960s, anti-Vietnam War protests were heating up on the campus. Although Dillinger’s lab was not the intended target of the infamous Sterling Hall bombing in 1970, it suffered the greatest damage. Dillinger’s post-doctoral student, Robert Fassnacht, was killed and the lab destroyed. It was a devastating loss for Dillinger. “He was close to all his students,” said former student Delbert Jones (’57 MS, ’65 PhD L&S). “Joe was a fine man who always had the best interest of his students at heart.” Dillinger continued to serve on the faculty until his death in 1975 at the age of 59.

Today, it is the positive influence of Professor Joe Dillinger that endures. The Dillinger family and a matching contribution from IBM established the Joseph R. Dillinger Teaching Award in the 1990s. Over the years, other grateful students and friends also have made gifts to the fund to support an outstanding teaching assistant in physics. The first recipient of the award was Mark Gehrke in 1996. “I very much enjoyed being a teaching assistant,” said Gehrke. “I had interested and motivated students.” Gehrke earned his master’s in physics in 1998 and now works in research engineering near Ann Arbor, Michigan.

The 2010 recipient is Vikram Adhikarla, a doctoral student who is a teaching assistant in the Department of Physics. His research in the Department of Medical Physics includes computational modeling of vasculature in relation to cancer tumors. “Receiving an award related to such a distinguished teacher and professor of the department makes me feel extremely honored and has left me pleasantly surprised,” said Vikram. “The award also motivates me to take up teaching later in my life.”

“It is always very good to have private support for graduate students,” said Baha Balantekin, chair of the Department of Physics. “But this gift is especially welcome as it honors the memory of Professor Dillinger.”

Scientist Turned Wordsmith Impacts Students

Theodore “Ted” Cohen has authored five novels that share his life experiences—facts wrapped in fiction—that many Badgers will recognize. Continue reading »

Theodore “Ted” Cohen has authored five novels that share his life experiences—facts wrapped in fiction—that many Badgers will recognize. Continue reading »

Whom Would You Honor?

The School of Education has created a program that makes it easy for you to recognize teachers and academic mentors. The Honor Your Teacher Campaign offers the opportunity to make a gift in honor of the educator who has made a profound impact on your life. Continue reading »

The School of Education has created a program that makes it easy for you to recognize teachers and academic mentors. The Honor Your Teacher Campaign offers the opportunity to make a gift in honor of the educator who has made a profound impact on your life. Continue reading »